https://blog.tensorflow.org/2018/07/move-mirror-ai-experiment-with-pose-estimation-tensorflow-js.html?hl=hi

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiCKDbHm-J8K9uoEjVaKLMxILOeo2sATU_5PhMwRKuzZ3Y_zdQx7mxbFYn8gihkYiBd8WDbqaoEH1rygAMPmHlr1fkSS8P8ciQkmqUa6FpRsFt1BrL6cnBmKqASIXqE4mWIVuckvYFyLms/s1600/movemirror1.gif

Move Mirror: An AI Experiment with Pose Estimation in the Browser using TensorFlow.js

Posted by Jane Friedhoff and Irene Alvarado, Creative Technologists, Google Creative Lab

Pose estimation, or the ability to detect humans and their poses from image data, is one of the most exciting — and most difficult — topics in machine learning and computer vision. Recently, Google shared

PoseNet: a state-of-the-art pose estimation model that provides highly accurate pose data from image data (even when those images are blurry, low-resolution, or in black and white). This is the story of the experiment that prompted us to create this pose estimation library for the web in the first place.

Months ago, we prototyped a fun experiment called

Move Mirror that lets you explore images in your browser, just by moving around. The experiment creates a unique, flipbook-like experience that follows your moves and reflects them with images of all kinds of human movement — from sports and dance to martial arts, acting, and beyond. We wanted to release the experience on the web, let others play with it, learn about machine learning, and share the experience with friends. Unfortunately we faced a problem: a publicly accessible web-specific model for pose estimation did not exist.

Typically, working with pose data means either having access to special hardware or having experience with C++/Python computer vision libraries. We thus saw a unique opportunity to make pose estimation more widely accessible by porting an in-house model to

TensorFlow.js, a Javascript library that lets you run machine learning projects in the browser. We assembled a team, spent a few months developing the library, and ultimately released

PoseNet, an open-source tool that allows any web developer to play with body-based interactions, entirely within the browser, no special cameras or C++/Python skills required.

With PoseNet out in the wild, we can finally release

Move Mirror — a project that is a testament to the value that experimentation and play can add to serious engineering work. It was only through a true collaboration between research, product,

and creative teams that we were able to build PoseNet and Move Mirror.

|

| Move Mirror is an AI Experiment that finds your pose and matches your moves with thousands of images from around the world |

Read on to get an in-depth view into how we made the experiment, what excites us about pose estimation in the browser, and the ideas on the horizon that we’re excited for.

What is pose estimation? What is posenet?

As you might guess, pose estimation is a pretty complex issue: humans come in different shapes and sizes; have many joints to track (and many different ways those joints can articulate in space); and are often around other people and/or objects, leading to visual occlusion. Some people use assistive devices like wheelchairs or crutches, which may block the camera’s view of their bodies; others might not have certain limbs; and still others may have very different proportions. We want our machine learning models to be able to understand and smartly infer data about all these different bodies.

|

| Here, you can see PoseNet’s joint detection results on folks who are using assistive devices (like canes, wheelchairs, and prosthetic limbs). |

In the past, technologists have approached the problem of pose estimation using special cameras and sensors (like stereoscopic imagery, mocap suits, and infrared cameras) as well as computer vision techniques that can extract pose estimation from 2d images (like

OpenPose). These solutions, while effective, tend to require either expensive and not widely distributed technology, and/or familiarity with computer vision libraries and C++ or Python. This makes it harder for the average developer to quickly get started

with playful pose experiments.

When we first encountered PoseNet, it was available via a simple web API, which was super exciting. All of a sudden, we could prototype pose estimation experiments quickly and easily in Javascript. All we had to do was send an HTTP POST request to an internal endpoint with our image’s base64 data — the API endpoint would send us pose data back with almost no latency. This hugely lowered the barrier to entry for making small exploratory pose experiments: just a few lines of JavaScript, an API key, and we were set! But of course, not everyone would have the capacity to run their own PoseNet backend, and (reasonably) not everyone would feel comfortable sending photos of themselves to a centralized server anyway. How could we make it feasible for people to run their own pose experiments without having to rely on our servers, or anyone else’s?

This was the perfect opportunity, we realized, to connect TensorFlow.js to PoseNet. TensorFlow.js would allow users to run machine learning models right in their browser — no server required. By porting PoseNet to TensorFlow.js, anyone with a decent webcam-equipped desktop or phone could experience and play with this technology, right from within a web browser, without having to worry about low-level computer vision libraries

or setting up complicated backends and APIs. Working closely with

Nikhil Thorat and

Daniel Smilkov of the TensorFlow.js team, Google researchers

George Papandreou and

Tyler Zhu, and

Dan Oved, we were able to port a version of the PoseNet model to TensorFlow.js. (You can read more about that process

here.)

A few things that made us super excited about PoseNet in TensorFlow.js:

- Ubiquity/Accessibility: Most developers have access to a text editor and a web browser, and usage of PoseNet is as simple as including two script tags in your HTML file — no fancy server setup required. You also don’t need any special high-res or infrared cameras or sensors to get data — in fact, we found that PoseNet still works well on low-res, black-and-white, and vintage photography.

- Shareability: Because everything can run in the browser, TensorFlow.js PoseNet experiments can also be shared in the browser super-easily. No need to make operating-system-specific builds — just upload your webpage and go.

- Privacy: Because all of the pose estimation can be done in the browser, that means none of your image data ever has to leave your computer. Rather than sending your photos to some server in the sky to do pose analysis on a centralized service (i.e. such as when you use a vision API which you may not control, or which may fail, or any number of things), you can do all the pose estimation on your device, controlling exactly where your image goes. With Move Mirror, we match the (x,y) joint data that PoseNet spits out with our bank of poses on our backend — but your image stays entirely on your computer.

Okay, enough tech talk: let’s talk design!

Design and Inspiration

We spent a few weeks just goofing around with different pose estimation prototypes. For those of us who came from C++ or Kinect-hacking, just seeing our skeleton reflected back to us

in our browser, using our webcam, was a pretty amazing demo on its own. We played with trails, puppets, and all sorts of other silly things before we landed on the concept that would become

Move Mirror.

It probably isn’t surprising to hear that a lot of us here in the Google Creative Lab are interested in search and exploration. In talking about what we could do with pose estimation, we were tickled by the idea of being able to search an archive by pose. What if you could strike a pose and get a result that was the dance move you were doing? Or — maybe even funnier — what if you struck a pose and got a result that was the same, but totally out of context for what you were doing? How could we find weird, serendipitous connections across the breadth of human movement — from martial arts to cooking to skiing to babies taking their first steps? How might that surprise us, delight us, and make us laugh?

We took inspiration from projects like

Land Lines (in which gestural data is used to explore similar lines in Google Earth) and the Cooper Hewitt

Gesture Match (which is an on-site installation that uses pose-matching to suggest items from the archive). Aesthetically, however, we were drawn in a much faster, more real-time direction. We loved the idea of having a constant stream of images respond to your movements, blurring folks from all walks of life together, connected by your movement. Inspired by rotoscoping and timelapse photography, as are used in

The Johnny Cash Project, and the trend of

selfie timelapses on YouTube, we decided to lean hard on the gas pedal and attack real-time responsive pose matching in the browser — a complex problem itself.

|

| Gif of The Johnny Cash Project, in which more than 250,000 people individually drew frames for “Ain’t No Grave” to make a crowdsourced music video. |

Building Move Mirror

Although PoseNet took care of the pose estimation for us, we still had plenty of things to figure out. The core experience is all about finding matching images to user poses, so that if you stand straight with your right arm raised up, Move Mirror finds an image where someone is standing with their right arm raised up. For that we needed three components: an image dataset, a search technique for that dataset, and a pose matching algorithm. Let’s break it down and look at each piece.

Building a dataset: searching for diversity

To create a useful dataset, we had to search for images that collectively covered a huge variety of human movement. There was no point in having 400 images of a person standing with a raised right arm if other poses were not represented in the dataset. To keep the experience consistent, we also decided we’d focus on finding only full-body images. In the end, we licensed a set of videos we thought represented not just a variety of movement, but also a diverse set of body types, skin tones, cultures, and physical abilities. We split these videos into about 80,000 still frames, then processed each image with PoseNet and stored the associated pose data. Next, let’s talk about the hard parts: pose matching and search.

|

| We parsed thousands of images through PoseNet. You’ll notice not all images are parsed correctly so we discarded a few to end up with a dataset of about 80,000 images. |

Pose matching: the challenge of defining similarity

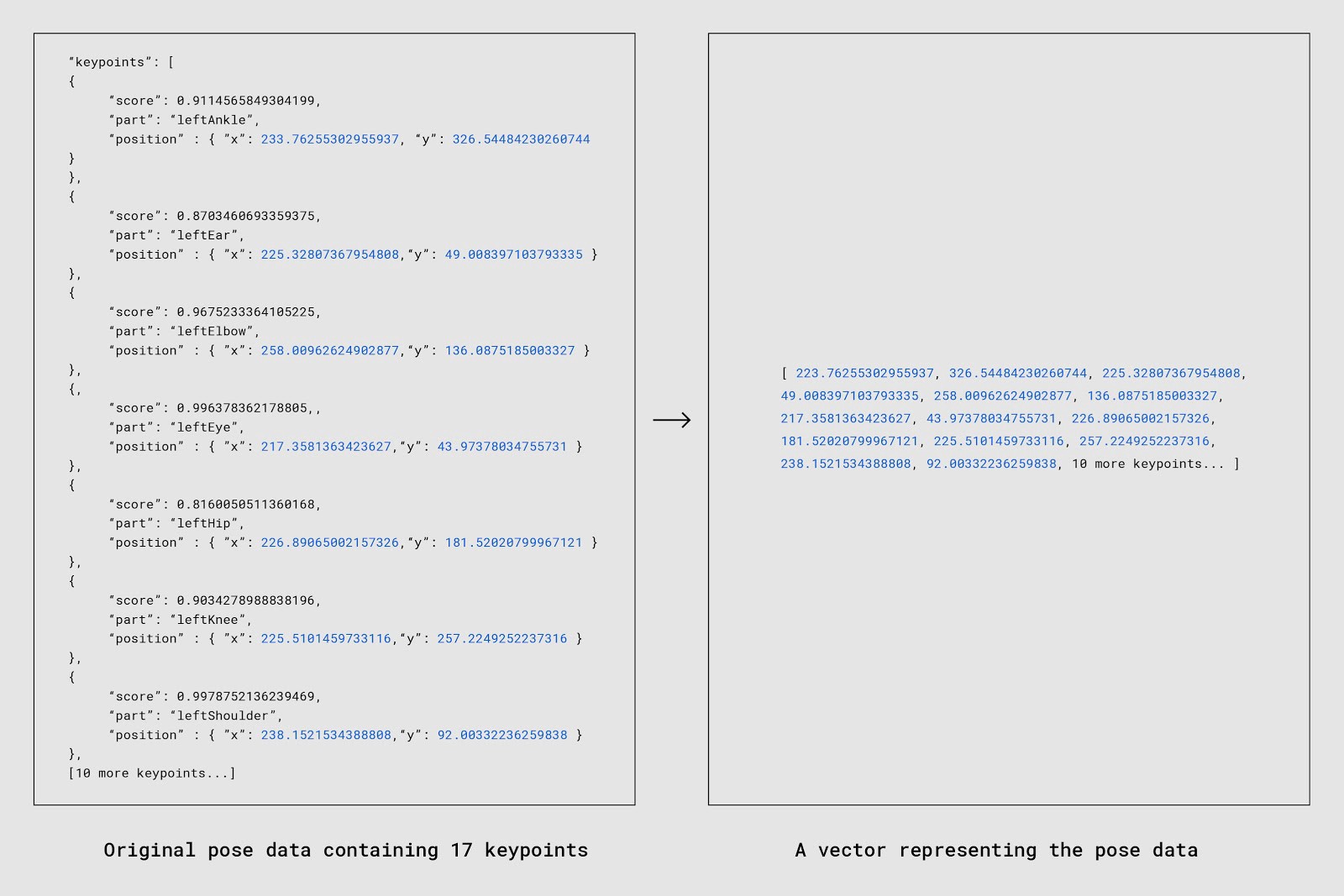

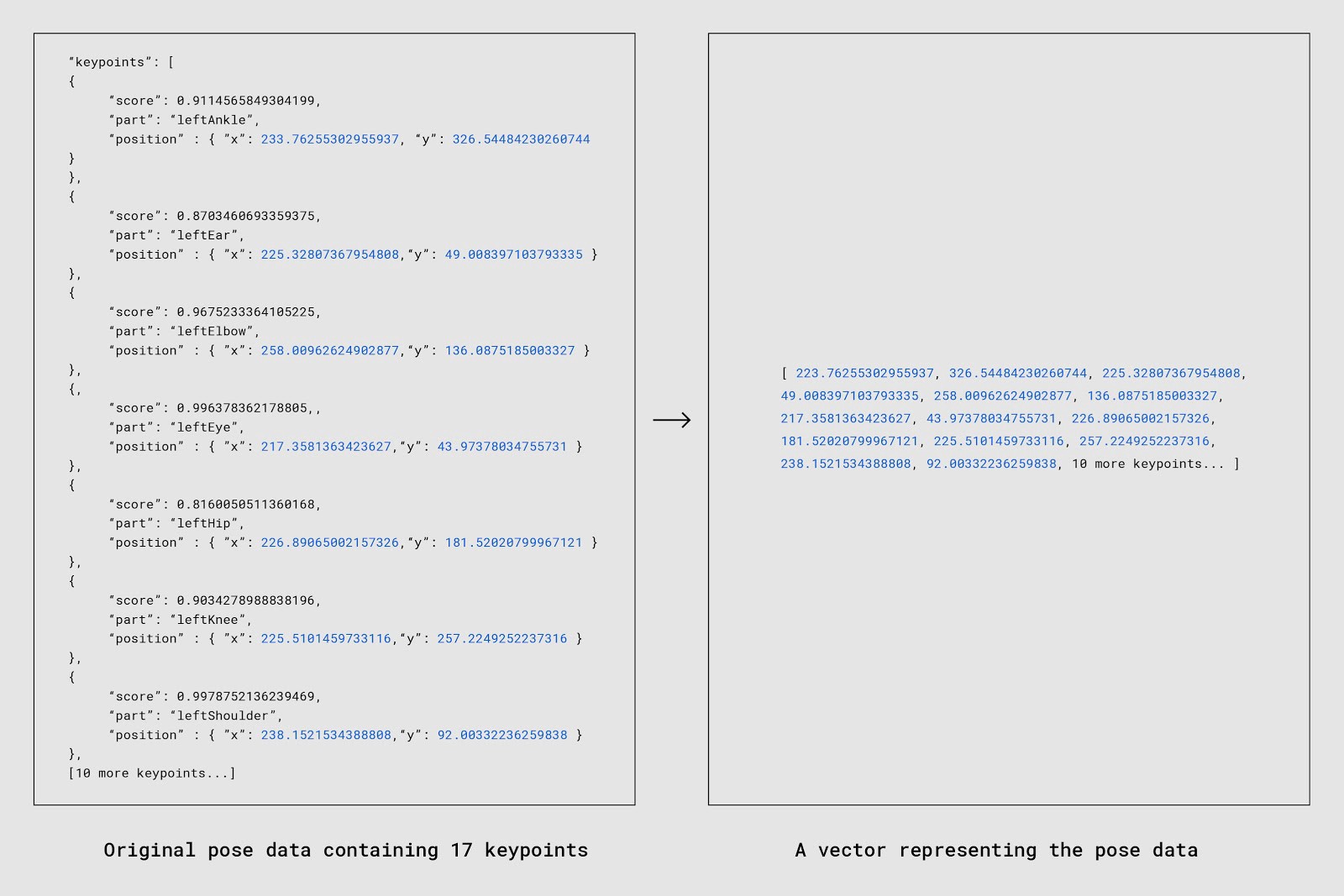

For Move Mirror to work, we first had to figure out how to define a ‘match’. A match is the image we return, based on the pose data we receive, when a user strikes a pose. When we talk about the ‘pose data’ coming out of PoseNet, we’re referring to a set of 17 body or face parts, such as an elbow or a left eye, that are called “keypoints”. PoseNet returns the x and y position of each keypoint in relation to the input image, plus an associated confidence score (more on this later).

|

| PoseNet detects 17 pose keypoints on the face and body. Each keypoint has three important pieces of data: an (x,y) position (representing the pixel location in the input image where PoseNet found that keypoint) and a confidence score (how confident PoseNet is that it got that guess right). |

Deciding what ‘similarity’ meant became our first hurdle. How should we decide how similar a set of 17 keypoints from a user is to a set of 17 keypoints from an image in our dataset? We tried a few different measures for similarity and settled on two that seemed to work well: cosine similarity and a weighted match taking into account keypoint confidence scores.

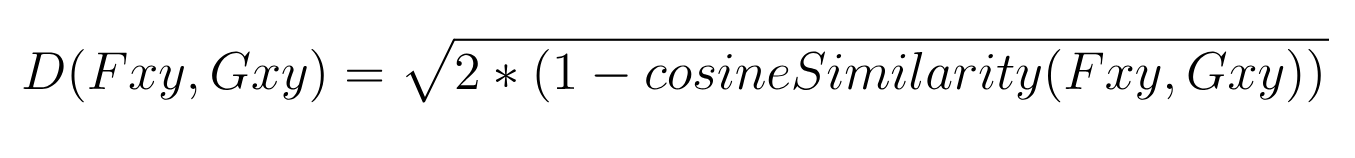

Matching strategy #1: cosine distance

If we were to convert each set of 17 keypoints into a vector and plot all of them in high dimensional space, our task of finding the two most similar poses would translate into finding the closest two vectors in this high dimensional space. This is exactly what cosine distance allows us to do.

Cosine similarity is a measure of similarity between two vectors: basically, it measures the angle between them and returns -1 if they’re exactly opposite, 1 if they’re exactly the same. Importantly, it’s a measure of orientation and not magnitude.

Although we’re talking about vectors and angles, it’s not limited to lines on graphs: you can use cosine similarity to, for example, get a

numerical similarity between two equal-length strings. (You may have indirectly used cosine similarity before if you’ve ever used

Word2Vec.) Indeed, it’s a super-helpful way to reduce the relationship between two high-dimensional vectors (two long sentences, or two long arrays of numbers) into a single number.

|

| A simplified version of Nish Tahir’s excellent example. Don’t worry if you don’t know vector math: the important thing to see is that we were able to turn two pieces of abstract, high dimensional data (5 dimensions, for 5 unique words) into a single, normalized number representing their similarity. |

Our incoming data was JSON, but we could easily compress those values into one-dimensional arrays, where each entry symbolized either the X or Y position of a keypoint. As long as we kept our structure consistent and predictable, the resulting arrays could be compared in much the same way. So that was our first step: changing our data from an object to an array.

|

| A snippet of the JSON coming from PoseNet, and a snippet of the flattened array of X and Y positions. (You’ll notice this array doesn’t take confidence into account — we’ll get back to that in a bit!) |

With that, we could use cosine similarity to get a similarity measure between our incoming 34-float array and any given 34-float array in our database. We could pop in our two long arrays and receive a much-easier-to-parse similarity score between -1 and 1.

Now, because all the images in our dataset can be of different widths/heights, and because each person can appear within a different subset of the image (top left, bottom right, center, etc.), we performed two additional steps to be able to compare the data consistently:

- Resize and scale: We used each person’s bounding box coordinates to crop and scale each image (and corresponding keypoint coordinates) to a consistent size.

- Normalize: We further normalized the resulting keypoints coordinates by treating them as an L2 normalized vector array.

Specifically, we use

L2 normalization for the second step, which just means we’re scaling the vector to have a unit norm (if you square each element in a L2 normalized vector and sum them up, the result is equal to 1). Compare these two graphs to get a sense of how the normalization transforms the vectors:

|

| A vector scaled with L2 normalization/td> |

The two steps described above can be thought of visually as follows:

|

| Steps taken to normalize Move Mirror data |

With the normalized keypoint coordinates (stored as a vector array), we can finally calculate the cosine similarity and perform a few

calculations detailed below to arrive at a

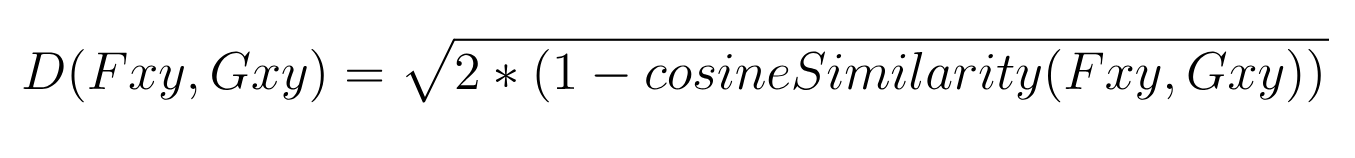

euclidean distance that can be interpreted as a cosine distance. The formula looks like this:

In the formula above, Fxy and Gxy are two pose vectors to be compared after L2 normalization. Moreover, Fxy and Gxy contain only x and y positions for each of the 17 keypoints — not the confidence scores for each keypoint.

The javascript gist looks like this:

// Great npm package for computing cosine similarity

const similarity = require('compute-cosine-similarity');

// Cosine similarity as a distance function. The lower the number, the closer // the match

// poseVector1 and poseVector2 are a L2 normalized 34-float vectors (17 keypoints each

// with an x and y. 17 * 2 = 32)

function cosineDistanceMatching(poseVector1, poseVector2) {

let cosineSimilarity = similarity(poseVector1, poseVector2);

let distance = 2 * (1 - cosineSimilarity);

return Math.sqrt(distance);

}

Neat, right? Let the matching commence!

Matching strategy #2: weighted matching

Well, almost. This approach still had a pretty big flaw. Our sentences in the cosine similarity example above — “Jane likes to code” and “Irene likes to code” — are static: we have 100% confidence as to what they are signifying. But pose estimation isn’t so cut and dry. Indeed, when we are trying to infer where a joint is, we almost never have 100% confidence in where it is. We can get really, really close, but unless we’re an X-ray machine, our likelihood of hitting exactly 100% confidence is low. Sometimes we can’t really see a joint at all, and have to make our best guess based on what else we know about the human body.

|

| Posenet returns a confidence score for each keypoint. The model predicts keypoints with a higher confidence score to be more accurate. |

Each piece of joint data returned thus also has a confidence score. Sometimes we are very confident of where a joint is (e.g., if we can see it clearly); other times, we have very low confidence (e.g., if the joint is cut off or occluded), to the point where our number must come with a big shrug emoji as a disclaimer. If we ignore these confidence scores, we are losing out on valuable data about our data, and we may give far too much weight and importance to data that we’re not actually that confident about. This creates noise that can lead to some really strange and arbitrary-seeming match results.

So, while the cosine distance technique was useful and produced good results, we felt we could do better by incorporating the confidence scores (the probability of that joint actually being where the PoseNet expects it to be). Specifically, we would like to be able to weight the joint data so that low confidence joints have less effect on the distance metric than high confidence joints. Google researchers

George Papandreou and

Tyler Zhu came to the rescue with a formula that could do precisely this:

In the formula above, F and G are two pose vectors to be compared after L2 normalization (explained in the previous section). Fck is the confidence score of the kth keypoint of F. Fxy and Gxy represent the x and y positions of the kth keypoint for each vector. Don’t worry if you don’t understand the whole formula — what’s important is to understand that we’re using keypoint confidence scores to improve our matching. The following javascript gist might illustrate this a little better:

// poseVector1 and poseVector2 are 52-float vectors composed of:

// Values 0-33: are x,y coordinates for 17 body parts in alphabetical order

// Values 34-51: are confidence values for each of the 17 body parts in alphabetical order

// Value 51: A sum of all the confidence values

// Again the lower the number, the closer the distance

function weightedDistanceMatching(poseVector1, poseVector2) {

let vector1PoseXY = poseVector1.slice(0, 34);

let vector1Confidences = poseVector1.slice(34, 51);

let vector1ConfidenceSum = poseVector1.slice(51, 52);

let vector2PoseXY = poseVector2.slice(0, 34);

// First summation

let summation1 = 1 / vector1ConfidenceSum;

// Second summation

let summation2 = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < vector1PoseXY.length; i++) {

let tempConf = Math.floor(i / 2);

let tempSum = vector1Confidences[tempConf] * Math.abs(vector1PoseXY[i] - vector2PoseXY[i]);

summation2 = summation2 + tempSum;

}

return summation1 * summation2;

}

This tactic gave us much more accurate results. Even when people’s bodies were occluded or out of frame, it was much better at finding an image with a pose approximating what the user is doing.

|

| Move Mirror tries to find a matching image given the pose estimated by PoseNet. The match accuracy is dependent on PoseNet’s accuracy as well as the diversity of the dataset. |

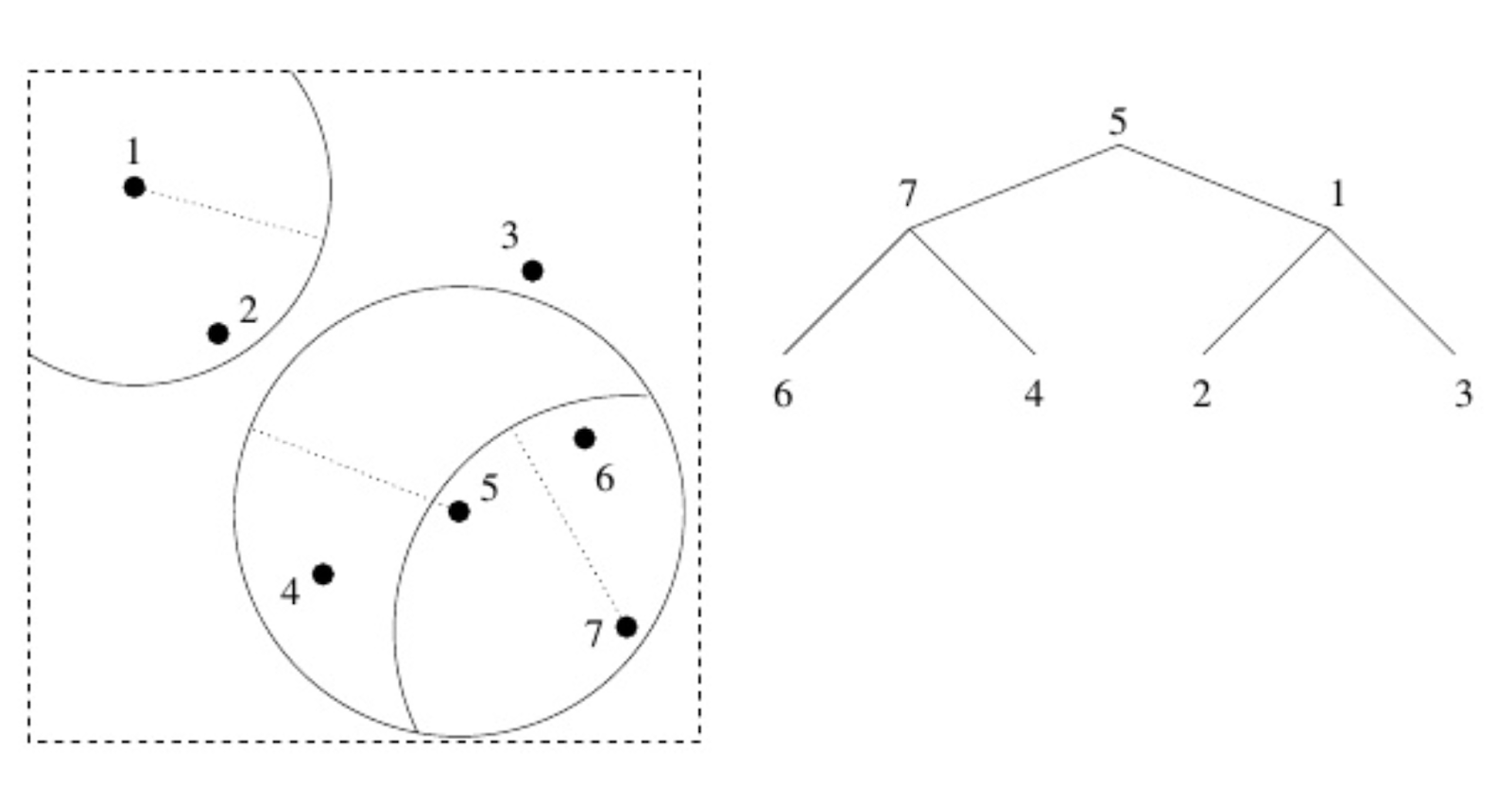

Searching pose data at scale: 80,000 images in ~15ms

Finally, we had to figure out how to do our searching and matching at scale. At first, it was easy to brute-force our matches: comparing an incoming pose to each entry in a database of 10 poses was no problem. But of course, 10 images wouldn’t be enough: in order to cover all sorts of human movement, we would need tens of thousands of images at a minimum. As you might expect, running a distance function on every single entry in a database of 80,000 leads to less-than-real-time results! So our next problem was figuring out how to quickly deduce which entries we could skip, and which entries were actually relevant. The more entries we could confidently skip, the faster we would be able to return a match.

We took a cue from

Zach Lieberman and the

Land Lines experiment, and used a data structure called a “

vantage-point tree” (javascript library

here) to traverse through our pose data. A vantage-point tree recursively splits data into two categories: those that are closer to some vantage-point than the threshold, and those that are farther away. This recursive sorting creates a tree data structure that can be traversed. (It’s kind of similar to a

K-D tree, if you’re familiar with those. You can read more nitty gritty detail about vantage point trees

here).

Let’s talk about vp trees in a bit more detail. Don’t worry if you don’t understand this next description completely — the important thing to understand is the general principle. We have a set of points in our data space and choose one (it can be at random!) to act as our root (in the image above, it’s point 5). We draw a circle around it, so some of the data is inside and some data is outside. We then choose two new vantage points: one inside our circle, and one outside it (here, 1 and 7). We add these two points as children to our first vantage point. Then, for both those points, we do the exact same thing: draw a circle around them, choose one point inside and one point outside their circle, use those vantage points as children, and so on. The key is that if you start at point 5, and find that point 7 is closer to where you want to be than point 1, you know you can discard not only point 1, but indeed its children as well.

With this tree structure, we didn’t have to compare every single entry on its own anymore: if the incoming pose wasn’t similar enough to some node in the vantage tree, we could assume that none of that node’s child nodes were going to be that similar, either. Rather than brute-force searching all the database entries, we could instead search by traversing the tree — allowing us to safely and confidently cut out huge swaths of our database that we knew weren’t going to be relevant.

The vantage point tree allowed us to rocket up our search result speed and make the real-time experience we were hoping for. It was a tricky needle to thread, but the experience of using it is just as magical as we hoped.

If you’d like to try these techniques yourself, here’s a gist of the javascript code we used to build the vp tree using the javascript library

vptree.js. While we used our own particular distance matching functions, we encourage you to explore and play with other possibilities — you just have to replace the distance function you pass onto the vp tree when building it.

const similarity = require('compute-cosine-similarity');

const VPTreeFactory = require('vptree');

const poseData = [ […], […], […], …] // an array with all the images’ pose data

let vptree ; // where we’ll store a reference to our vptree

// Function from the previous section covering cosine distance

function cosineDistanceMatching(poseVector1, poseVector2) {

let cosineSimilarity = similarity(poseVector1, poseVector2);

let distance = 2 * (1 - cosineSimilarity);

return Math.sqrt(distance);

}

function buildVPTree() {

// Initialize our vptree with our images’ pose data and a distance function

vptree = VPTreeFactory.build(poseData, cosineDistanceMatching);

}

findMostSimilarMatch(userPose) {

// search the vp tree for the image pose that is nearest (in cosine distance) to userPose

let nearestImage = vptree.search(userPose);

console.log(nearestImage[0].d) // cosine distance value of the nearest match

// return index (in relation to poseData) of nearest match.

return nearestImage[0].i;

}

// Build the tree once

buildVPTree();

// Then for each input user pose

let currentUserPose = [...] // an L2 normalized vector representing a user pose. 34-float array (17 keypoints x 2).

let closestMatchIndex = findMostSimilarMatch(currentUserPose);

let closestMatch = poseData[closestMatchIndex];

In

Move Mirror, we ended up using only the closest image matching a user’s pose. But for debugging we can actually traverse the tree and find, say, the top 10 or top 20 closest images. We actually built a debug tool to explore the data this way and it was very useful in helping us explore holes in our dataset.

|

| Our debug tool, with resulting images sorted by most to least similar (as determined by the algorithms above). |

In The Future

We had a ton of fun finding ourselves amongst swimmers, cooks, dancers, and babies, and there are plenty more fun places this technology can take us. Imagine searching through an archive of dance moves, or classic film clips, or music videos, all from the privacy of your living room (and the privacy of your browser!). Or imagine flipping this around, and using pose estimation to help guide home yoga workouts or physical therapy. Move Mirror is just one experiment in what we hope will be a Cambrian explosion of delightful and accessible in-browser pose experiments to come.

Try striking a pose on the

Move Mirror website. If you’re interested in playing with PoseNet for

TensorFlow.js, you can check out the

repo and a companion

blog post. You’ll also find more experiments on the

Experiments with Google website. We’d love to see what you make — and don’t forget to share your awesome projects using #tensorflowjs and #posenet!